One of the most universally applicable insights was first uttered in 1993 by the philosopher Method Man when he raspily rapped

Cash Rules Everything Around Me

He was absolutely right. In all industries, money influences behavior in surprising ways, and health care is no exception.

Thanks, Obama

Historically, healthcare has operated on a “fee-for-service” (FFS) model, where hospitals1 mirrored every other business: the more services they provided, the more money they made. This model isn’t ideal, though: if everyone constantly needs health care services, this means everyone is constantly sick. Furthermore FFS can create a financial incentive for health care providers to err on the side of overprescribing expensive treatments, regardless of whether they’ve been proven to result in better clinical outcomes. And they often don’t: healthcare is unique among industries in that technological advances often increase, rather than reduce, costs.2

It is also unique for a number of other reasons:

- The person receiving the service (i.e. the patient) doesn’t usually pay for it directly (insurers do)

- It’s a matter of life and death

In any model, fee-for-service or otherwise, insurers make money when their customers stay healthy, and lose money when they have to pick up the bill for sick patients.3 Thus, they want to keep us healthy, which is great, but they also prefer to exclude those likely to get sick from their membership entirely, which can result in the most vulnerable people either not paying for care4 or paying a debilitating amount.

In this system, insurers do great, hospitals (which can control how many services they provide) do ok, and patients do worse than you might think.

Given the choice, most people are probably more concerned with making sure the system works well for hospitals (which are almost always non-profits) and patients (which we all have been or will be at some point) than for insurance companies.

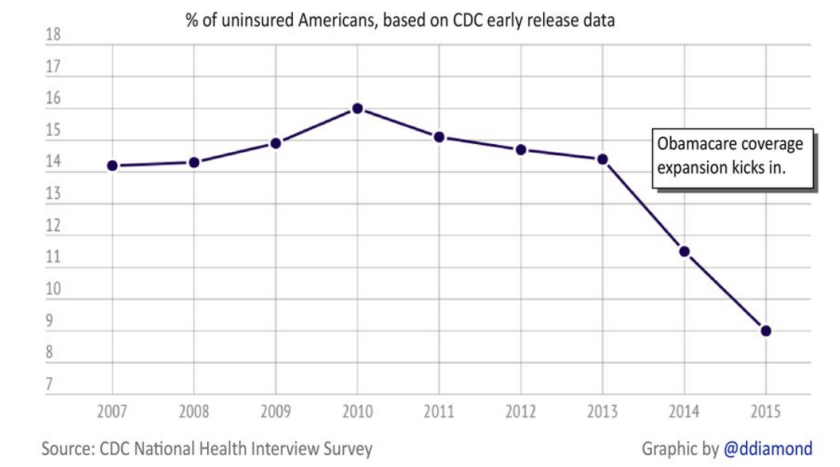

When the Affordable Care Act5 passed, it jumpstarted a transition to a value based system, where hospitals are reimbursed for effective—rather than frequent—treatment, and for keeping patients out of the hospital rather than in it. It has done this while expanding insurance coverage and forcing health care to adopt innovations every other industry adopted 10-20 years ago (i.e. using computers6).

Hopefully everyone agrees incentivizing the health care system to keep people healthy and out of the hospital is one of the least controversial things that could be done. If you can do so while ensuring more people have health care coverage, which the ACA has done, all the better.

Differing Vantage Points

The overall industry trend towards value has brought to light the often seething relationship between doctors and hospitals, which stems from a fundamental difference in perspective.

Being a doctor is among the most difficult and stressful jobs conceivable. Given the exacting environment, providers generally practice medicine for one reason: to help people (with a few very notable exceptions7). Thus, the doctor’s unit of analysis lies—as it should—at the level of the individual patient. If my doctor thinks there is even a slim chance ordering another test or procedure will help me, the last thing I want on his mind is “value.” I want him to order it.

A hospital administrator, however, has a different unit of analysis: the entire hospital. If every doctor orders every test, the hospital will go bankrupt, and won’t be able to provide care to anyone. Thus, “evidence-based” guidelines are a godsend because they can clarify when a give test or procedure should (and shouldn’t) be ordered.

However, there can never be a guideline for every scenario,8 and most agree that the physician should be empowered to make split second judgments based on his or her years of training and clinical experience, without fear of recourse for not following an “evidence based practice.”

Doctors have traditionally been completely independent, but are increasingly being employed by hospitals and health systems. With employment necessarily comes a loss of autonomy, and the push to follow evidence based guidelines can leave physicians with a bad taste in their mouths (“I don’t want to practice cookbook medicine!”), and the suspicion that finances are more important than patient care to hospital administrators.

Avoiding Disagreement When Everyone Agrees

Ultimately, hospital administrators and physicians both have the same goal: to provide care to patients. The issue between the two sides, then, is of communication and framing. Consequently, conversations between the two are likely to be less contentious if they are couched in patient care. Patient care resonates with both sides, and concentrating on a common goal is a well established tactic to build trust, which is the foundation of a strong relationship.

Though cash will undoubtedly continue to rule everything around us, the last thing hospitals and physicians need are further reminders.

Footnotes:

- Throughout this post, I’ll use the word hospital to mean any place where care is provided (e.g. health system, doctors office, minute clinic, etc.).

- I am looking at you, Da Vinci Robot, which costs 10X as much as a traditional minimally invasive procedure but has been found in 4000(!) studies to be no more effective.

- You can think of your insurance company as your gym, which wants you to pay your membership but never actually go. In other words, they want you to pay, but they don’t want to incur any of the costs associated with having you as a member. From an insurance company’s perspective, the ideal member is a healthy person who never gets sick or goes to the doctor.

- If someone doesn’t have insurance but needs care, a hospital isn’t going to turn them away. In fact, hospitals are required to provide “charity care,” or free health care, to those that cannot pay for it. Remember: the vast majority of hospitals are non-profit organizations.

- People prefer the ACA to Obamacare, which is strange because they are the same law.

- Seriously, though, hospitals couldn’t come up with this on their own, and needed the government to mandate that they “meaningfully use” information technology.

- i.e. Dr. Oz, for whom cash truly rules everything, including a desire to give sound medical advice.

- Though advances in artificial intelligence make me think I should never say never.