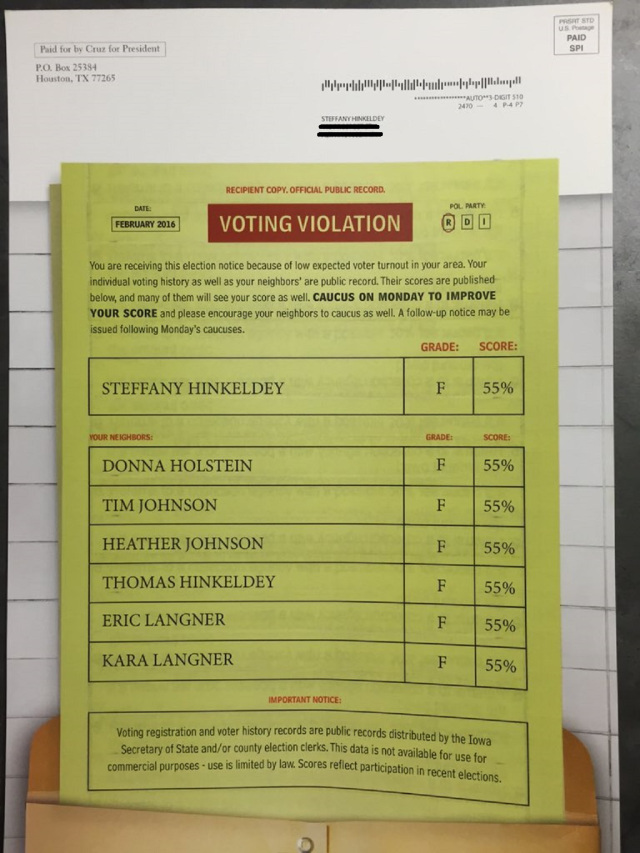

In the lead up to the Iowa Caucuses, presidential hopefuls use every trick in the book to turnout their supporters. Ted Cruz’s campaign took this to a new extreme recently by sending personalized “Voting Violation” letters to prospective voters that showed how they, and all their neighbors, had failing voter turnout scores.

This letter misapplies one of the most powerful forms of influence: social proof. Our actions are heavily influenced by what other people do, and this effect is heightened the more similar these “other people” are to us. Though this letter aimed to increase turnout, it is likely to have the opposite effect.

Robert Cialdini, who literally wrote the book on Influence, demonstrates why in a cleverly named experiment1 on how hotels could influence their guests to reuse towels. Compared to a standard message about reusing towels being good for the environment, guests told that a majority of other guests reused their towels were more likely to do the same. When told that the majority of people who had stayed in the same room they were currently in reused their towels, an even greater percentage of people did so.

When people similar to you do (or don’t) take a given action, you are likely to follow their lead.

Cruz’s Crummy Chicanery

If you learn that your neighbors have not voted in previous elections, this communicates that not voting is acceptable, making you less likely to do so. It’s easy to imagine someone who felt guilty about not voting in the past seeing this letter as an affirmation of the decision not to vote. If everyone isn’t doing it, why should I?

Rather than showing a comparison group of people who didn’t vote in the past (e.g. neighbors), finding a comparison group of people that did vote would have been more persuasive. It would reinforce the social norm that voting is the right thing to do. This comparison group could be based on geography (e.g. neighborhood, city, or county) or another demographic characteristic, such as age or gender.

A message like “Join your fellow Iowa Republicans in caucusing on Monday. In 2012, 70% of Republicans in your county caucused. Please join your fellow citizens and make a difference” would have been far more effective. Not only would it have exploited the principle of social proof (i.e. peer pressure), but it would also appeal to people’s natural motivation to be a part of something greater than themselves.

Behavioral science has profound potential for altering people’s behavior, a pleasing proposition to a power-hungry potential president. When using these techniques, however, candidates must be wary of achieving the exact opposite of their initial aims, an experience with which many politicians are quite familiar.

Footnotes:

- Goldstein, N. J., Cialdini, R. B., Griskevicius, V. “A Room with a Viewpoint: Using Social Norms to Motivate Environmental Conservation in Hotels”. Journal of Consumer Research 35.3 (2008): 472–482.

This is right on the money. Let’s hope Ted Cruz continues to get it wrong!

LikeLiked by 1 person

i enjoyed reading it – thanks!

lots of “i.e” distinguish with “e.g”

LikeLike

Glad you enjoyed it and good point about i.e. vs e.g.

LikeLike

Great post, Maor.

LikeLiked by 1 person